What wonderful news. Our innovative interdisciplinary Children Draw Talking paper has been accepted for publication today:

McLeod, S., Gregoric, C., Davies, J., Dealtry, L., Delli-Pizzi, L., Downey, B., Elwick, S., Hopf, S. C., Ivory, N., McAlister, H., Murray, E., Rahman, A., Sikder, S., Tran, V. H., & Zischke, C. (2025, in press). Children draw talking around the world. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. Manuscript accepted for publication.

Here is the short summary

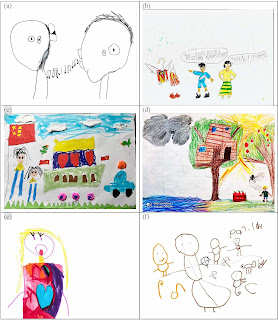

200 children from 24 countries drew who they talk to (friends, family, animals, professionals), when and where they talk (outside, at home), what they talk about (toys, animals, friends, family), and how they feel about talking (happy). These insights promote understanding of children’s communication and inform how children’s insights can be included in assessment and intervention.

Here is the abstract

Purpose. The purpose of this study is to determine how children from across the world draw themselves talking and to apply an interdisciplinary analysis to understand children’s perspectives to improve delivery of services at school.

Method. Participants were 200 children from 24 countries who submitted a drawing of themselves talking to someone using the Early Childhood Voices Drawing Protocol. Drawings were uploaded to Charles Sturt University’s Children Draw Talking Global Online Gallery. The participants were 2–12 years (M = 6.13), spoke 23 languages, and 28.5% of caregivers reported concerns about their children’s talking. A 16-member interdisciplinary research team analyzed the drawings using: descriptive, developmental, focal point, meaning making, and systemic functional linguistics transitivity analysis frameworks.

Results. Children could draw themselves talking. The participants’ age and ability to draw a human figure was strongly correlated. Most participants reported they felt happy about talking and drew themselves talking to one or more conversational partner(s), with focal points that included body parts and facial expressions, talking and listening, proximity to others, relationships and connections, and positivity and vibrancy. The cultural-historical meaning making analysis identified ten themes: relationships, places, actions, natural elements, human-made elements, cultural experiences, logical thinking, emotion, imagination, and concepts. The systemic functional linguistics transitivity analysis identified 71 processes, 134 participants, and 48 circumstances indicating richness in the children’s depictions of talking.

Conclusions. Children across the world can use drawing to communicate who they talk to (friends, family, animals, professionals), when and where they talk (outside, at home), what they talk about (toys, animals, friends, family), and how they feel about talking (happy). These insights promote understanding of children’s communication and inform how children’s insights can be included in assessment and intervention.

The children’s drawings are available here:

|

| 200 children from 24 countries drew themselves talking |